From our front-page news:

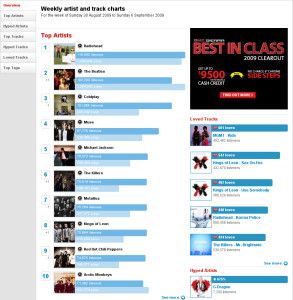

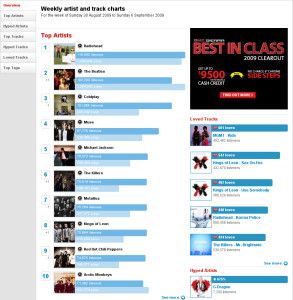

As I've mentioned in our news in the past, I'm a big fan of Last.fm, a site that not only keeps track of music I listen to, but also allows me to discover artists I'm not at all familiar with, based off recommendations that the site gives me. Because the site knows what I listen to, it can give better informed recommendations, and I can honestly say that I've discovered many artists thanks to the service, and I expect to discover many more going forward.

Such web services like this might seem simple on the front-end, but if you're familiar with how web services work, and servers, you're probably well aware that nothing is simple, and at Last.fm, there's a lot of mechanics at work. Wired found this out by interviewing the head of web development, Matthew Ogle. Details of the back-end isn't the only thing discussed, but things such as how the site pays artists is also tackled.

The technical bits are arguably the more interesting, though. Since the site launched in 2003, it's streamed over 275,000 years worth of music off its own servers, which is mind-boggling to think about. Delivering all that data of course requires powerhouse machines, but I found it surprising to find out that the company utilizes solid state disks (SSDs) quite heavily. Matthew didn't just mention SSDs, but even got specific about it, "The SSDs are made by Intel.".

Unfortunately, Matthew didn't go into precise detail about how much music the service holds, but he does say that they have "pretty much the largest library online", and that even if the song isn't on the servers, then there's still likely some information of the song somewhere on the site. Last.fm is like the Wikipedia for music. If a band you know has a song out there, it's likely listed on the site.

In addition to what's mentioned above, Matthew goes into much more detail about the rest of the business at Last.fm, so if you are interested in the site, or the future of the service, this interview is a recommended read.

"We have pretty strong relationships with most of the majors and they've definitely been interested at one time or another in pulling specific data to, for example, judge what an artist's next single should be. In aggregate, a lot of our data is very useful to them and we're obviously very careful about that. We are hardcore geeks -- died in the wool Unix nerds if you go back into our history -- so as a result our data is under lock and key.

Source: Crave UK

Such web services like this might seem simple on the front-end, but if you're familiar with how web services work, and servers, you're probably well aware that nothing is simple, and at Last.fm, there's a lot of mechanics at work. Wired found this out by interviewing the head of web development, Matthew Ogle. Details of the back-end isn't the only thing discussed, but things such as how the site pays artists is also tackled.

The technical bits are arguably the more interesting, though. Since the site launched in 2003, it's streamed over 275,000 years worth of music off its own servers, which is mind-boggling to think about. Delivering all that data of course requires powerhouse machines, but I found it surprising to find out that the company utilizes solid state disks (SSDs) quite heavily. Matthew didn't just mention SSDs, but even got specific about it, "The SSDs are made by Intel.".

Unfortunately, Matthew didn't go into precise detail about how much music the service holds, but he does say that they have "pretty much the largest library online", and that even if the song isn't on the servers, then there's still likely some information of the song somewhere on the site. Last.fm is like the Wikipedia for music. If a band you know has a song out there, it's likely listed on the site.

In addition to what's mentioned above, Matthew goes into much more detail about the rest of the business at Last.fm, so if you are interested in the site, or the future of the service, this interview is a recommended read.

"We have pretty strong relationships with most of the majors and they've definitely been interested at one time or another in pulling specific data to, for example, judge what an artist's next single should be. In aggregate, a lot of our data is very useful to them and we're obviously very careful about that. We are hardcore geeks -- died in the wool Unix nerds if you go back into our history -- so as a result our data is under lock and key.

Source: Crave UK